AI Capex and the Telecom Bubble: A Comparative Analysis

THE ABSTRACT

The topic of capital expenditure in AI has become highly visible as commentators continue to assert that AI has created a bubble analogous to the dotcom era. The prevailing narrative suggests that AI capex is directly parallel to telecom capex spending of the late 1990s, perpetuating concerns that the AI bubble will inevitably pop. Through our research, we found that this comparison requires substantial nuance: fundamental differences are separating the two megatrends, and concerns about AI capex among hyperscalers are driven more by sensationalism than by the historical factors that precipitated the dotcom crash.

However, our analysis reveals a more complex picture. While the core hyperscalers who represent 80-90% of all capex, Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet, maintain structural advantages through Free Cash Flow strength and legacy businesses that insulate them from telecom-era vulnerabilities, warning signs have emerged at the ecosystem's periphery. Meta, Oracle, and OpenAI each exhibit characteristics that warrant scrutiny. Most critically, we identify a new category of infrastructure providers through the AI neoclouds that display the most concerning parallels to 1990s telecommunications companies, including high leverage, customer concentration, vendor financing loops, and equity cross-holdings.

PArt I: The TEleCom Framework

Before examining AI capex, it is essential to understand the structural mechanisms that transformed the telecom boom into the telecom bust. The circular investments of 1990s telecoms were principled by three interconnected factors that artificially inflated revenues, enabled risky underwriting, and ultimately led to catastrophic value destruction.

The Three Pillars of Telecom Circularity

Capacity Swaps

Companies like Global Crossing, Qwest, Level 3, and Williams Communications would trade fiber capacity with each other at inflated prices. Company A would purchase capacity from Company B for $100 million, then Company B would purchase capacity from Company A for $100 million. Both entities recorded $100 million in revenue despite no net cash changing hands. These transactions created the illusion of robust demand and revenue growth while masking the fundamental lack of external customers.

Vendor Financing Loops

Equipment manufacturers including Lucent, Nortel, and Cisco provided financing or equity investments to telecom startups, who would then use that capital to purchase equipment from the same vendors. Furthering the risk, vendors would typically underwrite financings through use of debt, creating further exposure. The vendors booked immediate revenue while taking on risky startup equity or loans that often went unrepaid. This created a self-reinforcing cycle where vendors were effectively financing their own sales through the use of debt and high-risk assets, converting future risk into present revenue.

Equity Cross-Holdings

Companies made strategic equity investments in each other, then provided investee companies with preferential procurement contracts. The revenue appeared legitimate on income statements, but the underlying cash was merely circulating through equity positions on balance sheets. When one company's stock declined, it triggered margin calls and forced selling across the network of cross-holdings, creating cascading failures.

These three mechanisms operated in concert, creating a system where artificial revenue growth justified higher stock prices, which enabled more leverage, which funded more capacity swaps and vendor financing, perpetuating the cycle until external reality intervened.

Historical Benchmarks

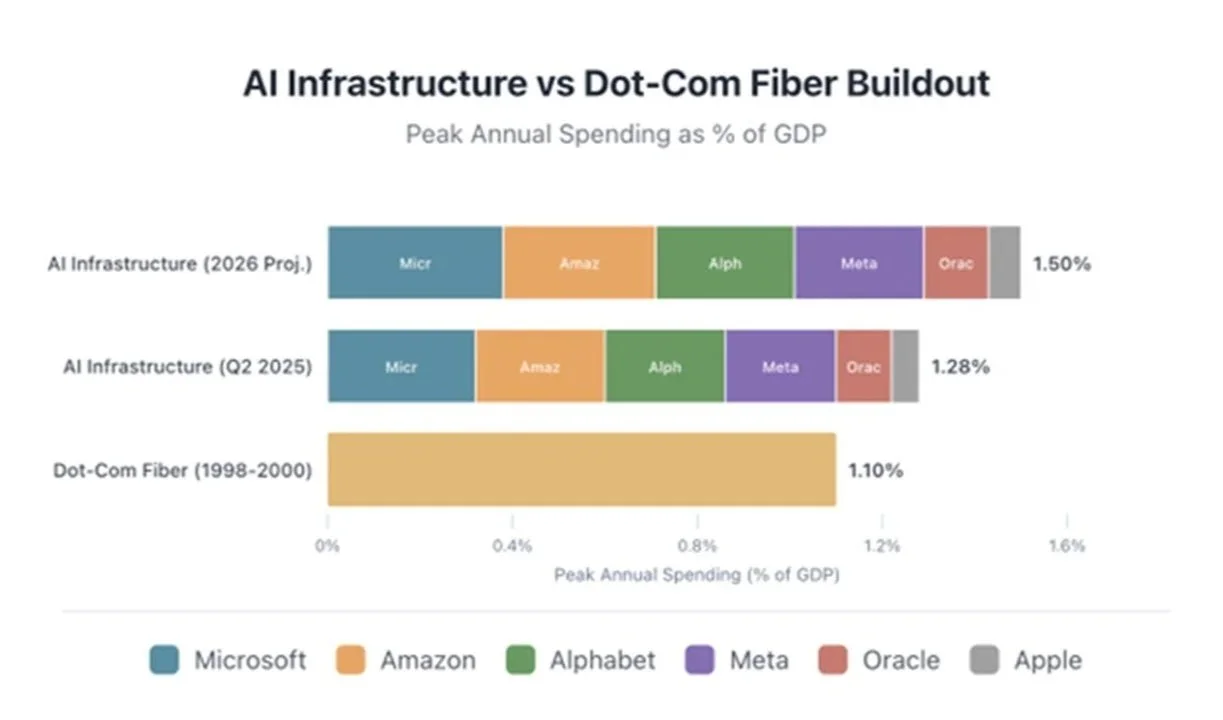

Peak annual telecom capex reached approximately $213 billion in 2000 (adjusted for inflation), with a total of over $500 billion spent between 1996 and 2000. At its peak, telecom capex reached 1.0–1.2% of U.S. GDP. The consequences of overbuilding were severe: even four years after the bubble burst, 85–95% of the fiber laid in the 1990s remained unused, earning the designation "dark fiber."

The fundamental flaw underlying this buildout was WorldCom's claim that internet traffic was doubling every 100 days, a gross misrepresentation that became gospel in the industry. In reality, traffic doubled approximately once per year, creating drastic overcapacity and stranded assets.

PART II: AI Capex Among Hyperscalers

The Current Landscape

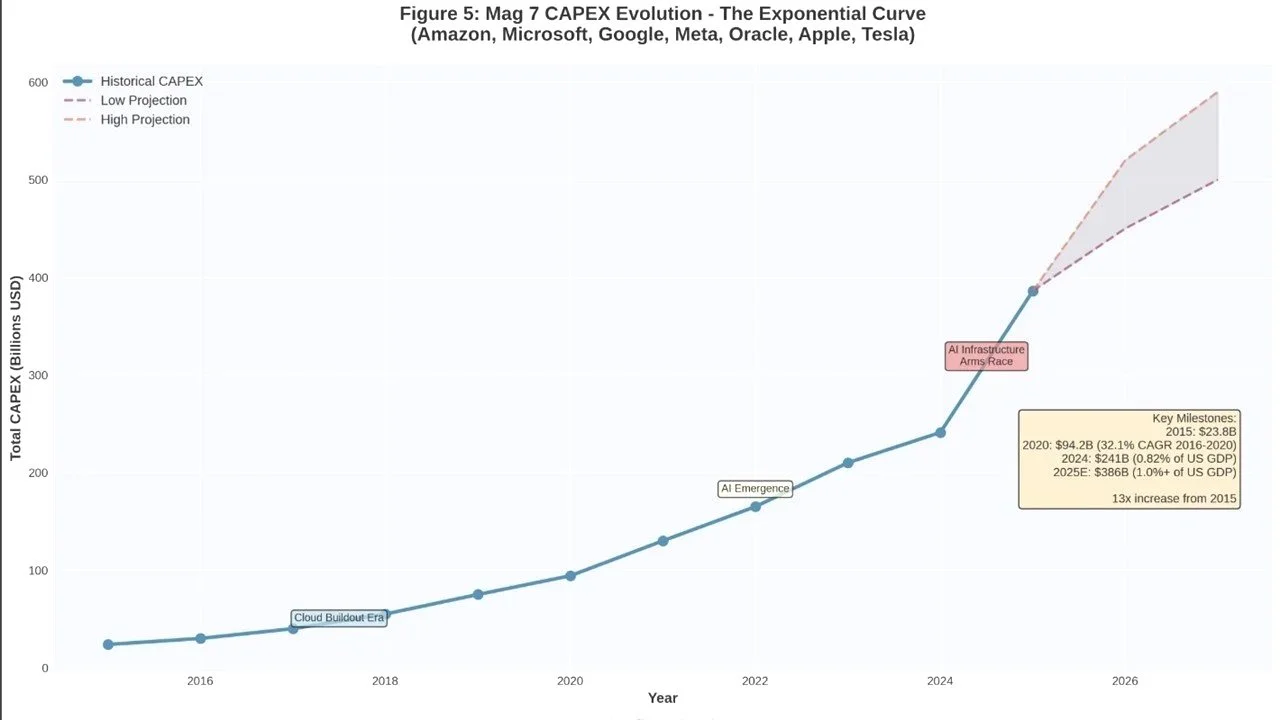

AI capex has fundamentally altered the dynamics of both public and private markets, with Nvidia's ascent to become the world's largest company by market capitalization, driven by real revenue scale and net income margins, serving as the quintessential example. AI capex spending in 2024 reached $241 billion through hyperscalers alone (Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, Oracle), and is projected to increase approximately 60% year-over-year to $405 billion for 2025. Growth is expected to continue through the back half of the decade, with expected spending of $1.15 trillion over the next three years.

Comparatively, AI capex has now reached 1.28% of GDP (Q2 2025 annualized) for the Magnificent Seven companies—exceeding the peak of telecom capex as a percentage of GDP. However, the comparison requires examination of fundamental structural differences in how this buildout is being financed.

Why Hyperscalers Differ from 1990s Telecoms

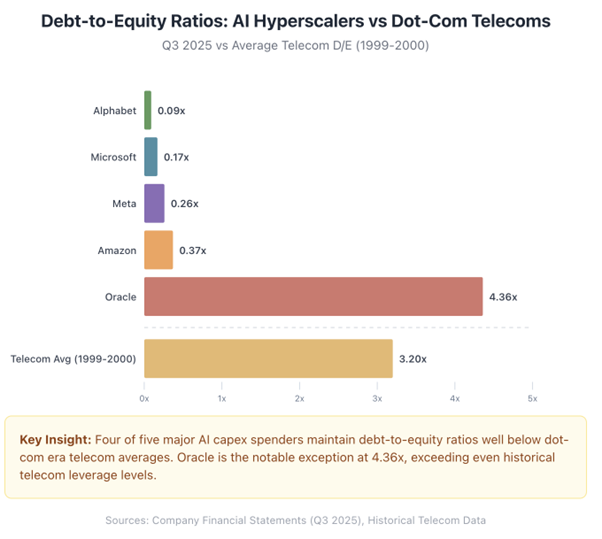

Conservative Leverage:

The primary drivers of AI capex are the largest companies in the world with sustainable revenues that invest off the balance sheet rather than through leverage. Of the four companies producing frontier models (Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta), the average debt-to-equity ratio is 0.23 as of September 2025. Six of the seven Magnificent Seven companies maintain negative net debt.

Debt-to-equity ratios as of Q3 2025

In stark contrast, during the dotcom era, industry average debt levels were extremely high, with most major telecom firms carrying massive debt loads financed through capital markets. Despite heavy AI capex, financial leverage among core hyperscalers remains conservative.

Proven Cash Flow and Monetization:

The hyperscalers are legacy businesses with strong cash flow and proven monetization pathways. Each maintains core business offerings that are highly independent from the AI capex buildout, even where tangential overlap exists in end products such as cloud services and enterprise software.

Counterintuitively to what headlines suggest, capex from hyperscalers is essentially building out their cloud services rather than speculative AI infrastructure. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud each account for 10–20% of revenue for their parent companies, with year-over-year growth rates of 25–30%.

If AI were to be entirely decoupled from the hyperscalers today, these companies would remain cash-flow-positive giants with highly sought products—similar to their positions in 2022, before the current AI investment cycle BEgAN.

Validated Demand:

The contrast with telecom demand projections is nuanced. WorldCom's claim of internet traffic doubling every 100 days created forecasts of 1,000%+ traffic growth that underwrote catastrophic overbuilding. Today's AI infrastructure investment is being validated by actual revenue: cloud infrastructure revenue is growing 25–30% year-over-year, and hyperscalers report genuine capacity constraints rather than excess supply.

But while the demand pipeline for hyperscalers is grounded in committed customer backlogs, there is a fundamental gap between AI infrastructure demand and the lagging AI application adoption. Data depicts only 23% of genAI adopters report measurable revenue or cost reductions, and that 42% of companies abandoned most of their AI initiatives.

The infrastructure demand is steady and plentiful, but it is underwritten by projections for growth in adoption of the underlying product of AI applications that is of concern; if growth metrics for the end-user are inconsistent with the steady growth of the infra buildout, overcapacity is possible.

The AI ecosystem must generate ~$600B in annual revenue to justify the current levels, but even the most optimistic estimates for major players depict a ~$500B gap. Until this gap between infra and application demand is bridged, there is a perpetual risk.

Part III: Warning Signs at the Periphery

While the core thesis holds for traditional hyperscalers building cloud infrastructure, several entities operating at the edge of this ecosystem exhibit characteristics reminiscent of the telecom bubble. Three cases warrant particular scrutiny: Meta, Oracle, and OpenAI.

Meta: Spending Without a Clear Revenue Pathway

Meta's 2025 trajectory has raised questions among analysts. The company spent hundreds of millions to poach AI talent, semi-acquihired the data-labeling company Scale AI for $15 billion, appointed a 28-year-old with limited AI background to lead its new Superintelligence Labs (polarizing senior AI talent), and saw its high-profile AI leader Yann LeCun announce his departure to launch his own startup, all amidst having no core AI product to substantiate their hyper-scale spending. Additionally, Meta announced and financed Project Hyperion, a large-scale data center underwritten by project debts and lease obligations.

Meta's AI spending extends beyond talent acquisition. The company raised its 2025 capex guidance to $70–72 billion (up from $66–72 billion), with 2026 capex potentially exceeding $100 billion. Unlike Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, Meta lacks a cloud services business and has no clear external revenue pathway tied to its AI investments.

Against our three guiding principles that distinguish the core hyperscalers through conservative leverage, monetization, and proven demand, Meta's 2025 behavior presents a contrast. While Meta's core advertising business provides a sustainable financing model, the leveraging and spending without a corresponding business model raises questions about the company's AI outlook—though this concern exists independently from the direct competitive pressure that AI is exerting on Meta's core social media business.

Oracle: Concentration Risk and Leverage

Oracle is targeting the hyperscaler infrastructure market, positioning itself alongside AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. Having operated as a legacy cloud and infrastructure provider with healthy free cash flow and moderate capex through 2024, the year 2025 marked a dramatic shift in both strategy and financial outlook

Oracle's free cash flow declined to -$5.9 billion in 2025, representing a -103% year-over-year change and marking the company's transition from positive to negative free cash flow. Oracle maintains significant financing leverage with a 4.36x debt-to-equity ratio, including an $18 billion debt commitment to fund AI infrastructure. Total debt stands at $105 billion against cash and marketable securities of $11.2 billion, resulting in a net debt position of +$94 billion.

What drove Oracle to increase its investment in 2025 was the widely reported story of its massive backlog, approximately $317 billion in remaining performance obligations (RPOs). However, this figure came with a significant asterisk: a single customer, OpenAI, is responsible for $300 billion of that backlog. Notably, this revenue does not commence until 2027 and is subject to the performance of a startup that is currently generating less than $20 billion in annual recurring revenue.

In summary, Oracle is highly leveraged, highly concentrated on a business model that remains projected rather than proven (OpenAI's), and is investing based on debt rather than balance sheet strength, all while spending comparatively far less than the top 4 hyperscalers, depicting the fragility of Oracle’s cash flow and displaying characteristics notably similar to telecom equipment vendors of the 1990s.

OpenAI: The Center of the Circle

OpenAI has drawn the most attention due to its position at the center of what may be a circular economy, albeit one designed for organizational sustainability rather than environmental sustainability.

The company has signed commitments totaling over $1.4 trillion through 2033, despite generating approximately $13 billion in annual revenue. HSBC projects OpenAI will remain unprofitable through 2030, facing a $207 billion funding shortfall over that period.

Examples of the circular structure of OpenAI's relationships :

Nvidia invests $100 billion in OpenAI; OpenAI commits to purchasing millions of Nvidia GPUs

AMD grants OpenAI warrants for up to 160 million shares (representing a 10% stake) in exchange for 6GW of GPU deployment commitments

Microsoft invests $13+ billion; OpenAI commits $250 billion in Azure spending

Oracle receives $300 billion commitment; OpenAI becomes Oracle's primary growth driver

Microsoft's training spend for OpenAI is paid via credits awarded as part of investment through non-cash revenue recognition

While these interconnected commitments appear concerning, OpenAI's strategy of high growth and high burn is emblematic of venture-backed startups. OpenAI is employing the same playbook that made Uber successful: extreme cash burn to scale value, subsidizing costs to drive adoption, and major strategic partnerships, but at a scale unlike any previously seen in history.

It is precisely this unprecedented scale that presents the greatest risk. OpenAI is already the largest "startup" in history, reaching a $500 billion valuation in its October 2025 financing round. With over $1 trillion in commitments for a company currently projecting $20 billion in ARR for 2025, the scale at which OpenAI operates (and the scale of capital required to maintain growth) now depends on continuous funding, as spend necessarily predates adoption due to the inherent nature of training costs and inference economics.

The overreliance of OpenAI on continuous cash injections, combined with vendors' reliance on OpenAI as a customer, creates inflated risk at an artificial scale. The circular nature dependent on projections and an undeveloped business model, high leverage and burn rate, and the lag between infrastructure investment and commercial adoption all present risk. Due to the circular nature of these relationships, companies dependent on OpenAI, such as Oracle, assume indirect risk, while vendors with diversified strategies, Nvidia, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, are better positioned to separate themselves by maintaining best practices.

Part IV: AI Neoclouds—The Most Vulnerable Segment

While hyperscalers exhibit structural advantages over 1990s telecoms, a new category of infrastructure providers, the neoclouds, displays characteristics that should concern investors.

Companies like CoreWeave, Lambda Labs, Crusoe, and TensorWave have emerged to serve AI compute demand, but their financial structures bear an uncomfortable semblance to the telecom model.

The Neocloud Business Model:

Neoclouds are GPU-focused cloud providers built specifically for AI workloads. They offer GPU instances at roughly one-third the hourly price of hyperscalers. Their competitive advantages derive from being independent providers capable of delivering instantaneous workloads, ranging from bare-metal access to software-enabled solutions across the market.

Across the market spectrum for neoclouds, there is a concentrated consortium of neoclouds that are legacy providers from the crypto trend – companies that pivoted from mining to deployment after building DCs and securing power contracts that proved more valuable in AI than mining. On the other hand, more novel performance-oriented players focused on dynamic solutions, true-software value-adds to GPU access and configurations, have sprouted from the market gaps in compute providers.

The neocloud value proposition is compelling: enterprises that cannot secure GPU capacity from hyperscalers, or that require more flexible arrangements than long-term enterprise agreements, turn to neoclouds for immediate access to compute. This has created genuine demand, but the financial structures underlying neocloud growth reveal significant fragility.

CoreWeave: A Case Study in Neocloud Risk:

CoreWeave, the largest neocloud, exemplifies both the promise and peril of this segment. The company reported $1.9 billion in revenue for 2024 with CoreWeave's latest guidance projects full-year 2025 revenue between $5.05 billion and $5.15 billion. CoreWeave's annual GPU-related capital expenditures (capex) for 2025 are projected between $12 billion and $14 billion, putting their capex at 4% of the total mag7 capex. While the company exhibits strong revenue, the structural risks are significant and merit detailed examination.

Customer Concentration:

CoreWeave derived 62% of its 2024 revenues from a single customer: Microsoft. This concentration risk mirrors the problematic dependencies of telecom equipment suppliers in the 1990s, where the fortunes of vendors were tied to a small number of customers whose own business models were unproven. If Microsoft reduces its reliance on CoreWeave, whether due to internal capacity expansion, strategic shifts, or macroeconomic pressures, CoreWeave faces an existential revenue gap.

Debt-Backed Growth:

CoreWeave has raised over $12 billion in total capital, with more than $10 billion in debt from lenders including Blackstone, Carlyle, and Magnetar Capital. These debts are secured against CoreWeave's stock of Nvidia GPUs, a depreciating asset class that loses value both from physical wear and from Nvidia's annual release of new, more powerful chips.

This financing structure creates a dangerous dynamic. GPU values decline predictably as new generations are released, yet the debt secured against those GPUs does not decline. CoreWeave must generate sufficient revenue to service debt while simultaneously reinvesting to maintain competitive infrastructure. If utilization rates fall or pricing power erodes, the company faces a classic asset-liability mismatch.

Circular Relationships with Nvidia:

Nvidia holds an equity stake of more than 5% in CoreWeave. More critically, in September 2025, Nvidia agreed to purchase $6.3 billion in cloud services from CoreWeave, essentially guaranteeing that any unsold capacity would be absorbed by Nvidia itself. This guarantee enables CoreWeave to purchase more Nvidia chips to build more data centers.

The circular nature is explicit: Nvidia invests in a company that buys Nvidia chips, secured by loans collateralized against those same chips, with Nvidia backstopping demand. This is functionally equivalent to vendor financing of the 1990s, where equipment manufacturers financed their own sales to recognize immediate revenue while assuming longer-term credit risk.

Mapping Neoclouds to the Telecom Framework

The neocloud segment displays all three characteristics of 1990s telecom circular investments, updated for the AI era:

Capacity Swaps (Modern Version):

In the telecom era, companies like Global Crossing and Qwest traded fiber capacity at inflated prices, with both parties booking revenue despite no net cash changing hands. The modern equivalent operates through workload shifting: HuggingFace leases from Lambda Labs, who leases from CoreWeave, who gets backstopped capacity from Nvidia. Each provider books revenue, but the ultimate end user is three layers down, creating a value chain that double or triple counts revenue across three different providers.

The structure creates mutual dependency without genuine external demand growth. Revenue circulates within a closed ecosystem where the ultimate customer's ability to pay depends on the continued willingness of revenue recipients to invest. When telecom companies engaged in capacity swaps, the reckoning came when external demand failed to materialize at projected levels. For neoclouds, the question is will this chain of command generate sufficient commercial revenue to honor their commitments.

Vendor Financing Loops

The 1990s pattern saw Lucent, Nortel, and Cisco provide financing to telecom startups who used the capital to buy equipment from the same vendors. The modern equivalent is nearly identical: Nvidia invests in neoclouds, which use the capital to buy Nvidia GPUs, which serve as collateral for Wall Street loans, which fund additional GPU purchases. However, the key difference between then vs now is that Nvidia, Microsoft, and other vendors are financing these investments via Free cash flow rather than debt, alleviating the capital risk associated with the leveraged loops of the 90s.

In contrast, The Financial Times reported that Wall Street has loaned more than $11 billion to neocloud companies based on their possession of Nvidia chips. This creates a fragile chain of dependencies: if GPU prices decline (due to new product releases, reduced demand, or competitive pressure), collateral values fall, potentially triggering margin calls or covenant violations. Meanwhile, Nvidia books sales that are effectively financed by the downstream capital structure rather than by end-customer demand.

The vendor financing loop is self-reinforcing until it isn't. Nvidia's revenue growth includes sales to entities whose ability to pay depends on continued capital markets access and Nvidia's own investment. This creates systemic risk that is not apparent from any single company's financial statements, and exposes vulnerabilities that while distanced from Nvidia, Microsoft, and Amazon, has kinks that could take out this emerging category that is heavily-embedded in nextgen AI companies.

Equity Cross-Holdings

In the telecom era, companies made strategic equity investments in each other, then awarded investee companies preferential procurement contracts. Revenue appeared legitimate but was merely circulating through equity positions.

The modern AI ecosystem exhibits analogous patterns: Nvidia holds equity in CoreWeave, Lambda Labs, and other neoclouds. Hyperscalers are “strategically investing” across numerous neoclouds such as Nscale and Microsoft, marking an investment that is redeemed through primary consumption. Microsoft is both a customer of CoreWeave and an investor in OpenAI (CoreWeave's largest customer). AMD has granted equity to OpenAI in exchange for deployment commitments. The value of each company is increasingly tied to the financial health of the others.

This web of cross-holdings creates correlated risk that is difficult to hedge and may not be fully appreciated by investors analyzing individual securities. A stress event at any node, such as a significant customer loss at CoreWeave, funding difficulties at OpenAI, a deceleration in Nvidia's growth, could propagate through the network of relationships, amplifying rather than absorbing shocks. While Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are protected due to their diversified revenue streams and customer compositions, a single node failure would cause a network of neoclouds to crash.

Additional Neocloud Vulnerabilities

Beyond the three-pillar framework, neoclouds face additional structural challenges that differentiate them from the hyperscalers:

Asset Depreciation Dynamics

Hyperscalers deploy GPUs as one component of diversified infrastructure supporting multiple revenue streams. If AI workloads decline, the same infrastructure supports general cloud computing, enterprise software, and consumer services. Neoclouds, by contrast, have single-purpose infrastructure: GPU capacity for AI training and inference. If AI demand disappoints projections, or simply grows more slowly than expected, neoclouds face stranded assets without alternative use cases.

Moreover, Nvidia's rapid product cadence creates continuous depreciation pressure. The H100 chips that commanded premium pricing in 2024 face competition from B100 and subsequent generations. Neoclouds must constantly reinvest to maintain competitive offerings, creating a capital expenditure treadmill that hyperscalers can more easily absorb given their diversified business models – all while discounting the extension of Google’s pending external sales of TPUs, creating supply scrutiny for over-contracted GPU-native neoclouds.

Pricing Power Erosion

Neoclouds initially benefited from GPU scarcity, commanding premium prices for immediate availability. As hyperscalers expand capacity and additional neoclouds enter the market, pricing power is likely to erode. CoreWeave's current pricing advantage (roughly one-third of hyperscaler rates) may narrow as competition intensifies, compressing margins precisely when debt service obligations require sustained profitability.

Counterparty Quality

The hyperscalers' largest customers are established enterprises with proven business models and creditworthy balance sheets. Neoclouds, by contrast, derive substantial revenue from AI startups whose business models remain unproven. When CoreWeave reports that OpenAI represents a significant portion of its committed revenue, investors should recognize that this revenue depends on OpenAI's continued ability to raise capital and grow into its valuation, neither of which is assured.

Part V: Conclusion

AI infrastructure investment is not monolithic. The thesis that AI capex differs fundamentally from telecom capex holds for the core hyperscalers of Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet who possess balance sheet strength, proven business models, and diversified revenue streams. These companies could absorb significant AI investment losses without existential risk. Even if AI fails to deliver projected returns, the infrastructure built will likely find alternative uses, much as dark fiber eventually enabled the cloud computing revolution of the 2010s.

However, the edges of this ecosystem exhibit warning signs that investors should not ignore:

Meta is spending aggressively on AI without a clear external revenue pathway, echoing its metaverse missteps

Oracle has concentrated its future on a single customer (OpenAI) while taking on significant leverage

OpenAI sits at the center of circular investment structures, with commitments far exceeding its revenue capacity

Neoclouds display the most telecom-like characteristics: high leverage, customer concentration, vendor financing loops, and equity cross-holdings

The critical difference from 1990s telecoms is that the core infrastructure providers are financially sustainable and are not using leverage, the one commonality between every financial crash in history. If the AI investment cycle disappoints, it will likely claim the peripheral players, the neoclouds, the over-leveraged enterprise customers, and the companies with concentrated exposure, all while the hyperscalers emerge with depreciated but functional infrastructure. The lack of leverage contains the destruction, isolating the risk to the business segments correlated to the assets, rather than overweighted leverage that would tie any delays or overcapacity to the full corp.

The evidence suggests a bifurcated outcome. The hyperscalers are likely building durable infrastructure that will generate returns over a longer time horizon than current market expectations may reflect. The neoclouds and circular investment structures, however, display the characteristics that preceded the telecom crash: leverage against depreciating assets, revenue recognition that depends on continued capital formation, and equity cross-holdings that create correlated rather than diversified risk.

Investors would be well served to distinguish between these segments rather than treating "AI infrastructure" as a monolithic category. The hyperscalers' AI investments are a calculated bet by companies that can afford to be wrong. The neoclouds' AI investments are an existential bet by companies that cannot.

Credit to Chase Seklar for the research, analysis and writing piece.

With review and insights from Jack Leeney